If you’re brand new to guns (or need a refresher) and want a non-political and rational “for dummies” introduction, this guide is for you.

Maybe you thought you’d never even own a gun until recently. Or you fired your cousin’s shotgun that one time out at the farm 20 years ago and want a refresher before taking on the serious responsibility of gun ownership.

Millions of people of all walks of life have been buying firearms in record numbers as more rational people reject the culture war around this topic and recognize the need for self-defense is still very real, even in an ‘advanced’ society. Women, liberals, urbanites, and people of color are some of the fastest-growing groups of firearm owners, for example.

Regardless of politics or background, you are welcome here. We believe in modern and responsible gun ownership — and think our communities and civil debates will be much better off if people at least accurately understood the topic of firearms before arguing about or fearing them.

Critical gun safety rules

Before we talk about anything else, you must commit to these simple but very important rules:

- Treat every firearm as if it’s loaded until you personally know it isn’t.

- Only point the firearm at things you are willing to destroy.

- Always be sure of your target and what’s behind it.

- Only put your finger on the trigger / inside the trigger guard when you are ready to fire.

Modern, quality firearms do not just fire on their own, even if dropped or bumped. 99.9% of gun accidents are caused by human error. By strictly following those rules, you don’t allow the circumstances where something bad can happen to begin with.

And it’s not the sort of thing where people get more relaxed with those rules as they become more experienced — in fact, the most advanced gun owners are typically the most stubborn about these rules because they know how important this framework is. That’s why you’ll hear old-timers angrily call out things like “muzzle discipline!” at the shooting range when someone new waves their barrel in the wrong direction.

It is your responsibility that firearms are safe, secure, and locked away from people or children who shouldn’t get to them. There are 1.7 million children in the US that live in homes with loaded but unlocked firearms. There are often serious legal punishments if you are careless with a gun, like leaving a loaded gun where a small child can access it.

The basic steps and gear you need

If you just want to go from “never had a gun” to “the bare minimum to protect me and be responsible”, this is a typical set of needed gear and steps to take:

-

- Read this guide and the best first guns guide so you have general ideas of what you want to end up with.

- Go to a local gun store or shooting range where you can work with a salesperson or instructor to try firing some weapons before choosing which to buy.

- Better yet, go with a trusted buddy who can loan you and teach you with their gear.

- When you buy, the firearm should come with a wire safety lock that loops through the chamber and magazine, making it physically incapable of firing. It may also come with a good-enough storage/carrying case you can use until buying a proper one.

- If you live in a household with at-risk people (kids, suicidal, handicapped), get a lockbox or gun safe to keep the gun and ammo out of the wrong hands.

- Buy ammo. You’ll use at least a few hundred rounds to practice with and get to know your weapon. It’s okay to buy cheaper rounds while you’re learning the ropes.

- Read the manual to learn how to make your specific firearm safe, how to load and unload it, whether the manufacturer suggests any steps for breaking it in, and how to perform a basic “field cleaning” (the maintenance you’ll do after a day of shooting).

- Buy a gun cleaning kit specific to your caliber.

- You’ll need an ear and eye protection (unless you wear sturdy glasses).

- Sign up for a local beginner’s class, which can be as simple as a one-hour lesson on a weekend afternoon. If you go to a shooting range outside of an organized class, don’t be afraid to ask for help.

- You don’t need to become a gun-slingin’ marksman, but you do need to feel proficient. A chaotic, emotional emergency is not the time to be fumbling with a gun. Spend a few days learning the basics, and try to dust off the cobwebs once a year — shooting accurately and safely is a diminishable skill, meaning it needs a little practice once in a while.

How to buy a gun

You can buy in person or online. If you’re totally new to firearms, experts suggest you buy in-person because you can feel how different models fit in your hand and ask questions.

Some gun stores and shooting ranges allow you to rent various guns. That’s a great idea for new shooters so you can get a feel before you buy.

And if you’ve never shot before, don’t worry! Stores love new shooters because you’re a new customer that will keep buying new toys. Just say you’re new at this and looking for help.

Don’t be intimidated by going into a gun shop due to cultural differences. Even if you’re the most pride-flag-waving liberal with your Bernie/Warren 2020 shirt on, any store worth your business will treat you with the same respect as a cowboy in an NRA hat.

Thankfully, the vast majority of legit businesses conduct themselves this way. If they don’t, then say thank you, leave, and share your experience on review sites.

If you do buy online, buy something new from a legit source. There are websites where individuals can sell guns to each other (which still goes through a background check). There are bonafide people and good deals in those marketplaces, but as a new shooter, you probably don’t know enough yet to spot the really bad deals. And once you find out it’s probably too late. Guns do go through a lot of wear and tear, after all.

Legal process

Different states and cities have wildly different laws about the types of guns you can buy, who can buy them, what you can do with them, and so on. Some places like San Francisco, Chicago, and D.C. try to ban most or all guns altogether.

Some general requirements:

- Over 21. Some areas allow people 18-21 to buy rifles and shotguns for hunting.

- Have not been convicted of a felony.

- Have not been declared mentally incompetent.

- Are not using medications or drugs that will impair your ability.

In almost all cases there will be a criminal background check. You’ll fill out a form and the store will run you through a federal database that usually only takes a few minutes to verify.

Cannabis: Note that even if you live in a state with legal marijuana, it’s still a crime at the federal level. These forms will ask if you are a “user of illegal drugs including marijuana.” There are no drug tests or verification.

Every gun has a serial number. Some states require you to register your gun and serial number in a government database.

Some states require a waiting or “cooling off” period. This means you pick your gun, pay for it, and do the background check but then you can’t take it home for a while. The political thinking is that if someone is angry and walks into a store to buy a gun, by making them wait 7-10 days to carry it home they will cool off and not commit whatever crime they were intending.

Basic ammo terms: bullets, calibers, and clips vs magazines

Since the whole point of a gun is to make a chunk (or chunks) of metal fly downrange and hit a target, we’ll start there, with the ammunition.

What many people call a bullet is actually called around. Like a “round” of drinks. But you’ll still hear people use the word bullet as slang for the whole cartridge.

A bullet is the specific part of the round that flies down the barrel and through the air to your target. During the firing process, other parts of the round are left behind and ejected as waste.

Other parts of the round are the casing, which is typically a brass, steel, or plastic housing that holds everything together. “Casing” and “brass” are the two most common lingo names.

Every round has gunpowder inside. That powder is ignited by a primer. That primer is a distinct circle in the middle of the base/rear on most ammo types. The popular and small .22 LR ammo, however, uses “rimfire” where the spark happens from smacking on the outer lip of the casing, rather than a distinct primer in the middle.

Shotgun ammunition is a little different because it fires lots of little projectiles instead of one bullet. That’s why shotguns are used in bird hunting — it’d be too hard to hit a flying bird with just one pellet, so you fire a bunch of pellets at once that spray out in a larger zone.

Shotgun ammunition is called a “shell,” or “shotshell”, and the bullets are called “shot.” But the principles are the same. You have a casing with a primer, gunpowder, and then the projectiles that are launched down the barrel.

Some types of guns — particularly revolvers and shotguns — are designed to hold a few rounds of ammo inside the main body. Other types hold the ammo in a separate, detachable housing that you load into the main body of the gun.

Revolvers don’t use detachable magazines because the ammo storage is built right in.

Those detachable containers are called magazines. Many people make the mistake of calling those clips, but a clip is a specific type of old-school housing you likely won’t ever use.

Most states in the US limit the size of magazines to 10, 15, or 30 rounds in a single container. Their thinking is that by limiting how many rounds are in a single magazine, it makes it harder for a criminal to shoot lots of bullets since they have to take the time to replace an empty magazine with a new one. But that also creates limitations in something like a home-defense situation, too.

Bullet sizes (ammunition types and calibers)

Let’s say you know you want to get a pistol. One of the next big decisions is deciding what kind and size of ammunition you want to shoot.

Since the whole point is to sling metal downrange at a target, what metal you’re slinging can have an impact on everything else: how far it can go, how fast, what kind of sound it makes, what kinds of materials it’s meant to punch through, what the kickback feels like on your arm and shoulder, etc.

Click to expand

The way people identify one size versus another is by “caliber”, which is usually defined by the diameter of the casing. eg. a .308 round is wider than a .223.

There are other measurements that might matter as well, such as the length of the casing. So sometimes you’ll see a label like “9×19” which means the diameter is 9 and the length is 19. But usually, the length is standardized and implied — eg. people know that a .223 is always 2.26 inches long, so the ammo box only needs to say “.223”.

Unfortunately, it won’t always be measured in millimeters or even follow a logical pattern. Because America is stubborn and refuses to join the rest of the world, sometimes things are measured in imperial and sometimes in metric. You’ll eventually learn the equivalent matches, like how the .223 inch imperial measurement is essentially the same as the 5.56 mm metric measurement — that’s the caliber the NATO military organization has standardized around so they can share supplies across different countries and units.

Sometimes the differences seem small, like the 9 millimeters round vs. the 10 millimeters round. But these are precision-built machines with exploding parts, so every fraction of a millimeter or extra grain of gunpowder matters.

There will often be a word or name after the numerical part of the caliber, like “.223 Remington.” For example, Remington is a gun company and designed the popular .223 Remington round used in AR-15s. But the specs are open source. You don’t have to use that round in a Remington gun and plenty of non-Remington companies now make the .223 round.

Shotgun ammo sizes (gauges) work differently

Shotgun ammo types are simpler in that there are fewer to choose from (only about eight). But the naming convention is often more confusing than a standard pistol or rifle bullets, and in many ways is a leftover from before the industrial revolution.

By far, the two most common shotgun sizes are 12 gauge and 20 gauge. A 12 gauge is bigger than a 20, however.

Imagine you start with a one-pound block of lead and want to make spherical pellets to use as shot in a shotgun shell. The bigger you make each ball, the fewer balls you’ll be able to make from a single one-pound block. That’s why the gauge number goes down as the shot size goes up.

Another way to think about it: it would take 20 lead balls with the same diameter as the barrel of a 20-gauge shotgun to weigh one pound.

There are other words involved in shotshell labeling, such as “Buckshot” or “Birdshot.” We go deeper into this in other guides, but the general idea is the label means what they’re meant to hunt. Taking down a buck (deer) takes more force than a bird, so buckshot is configured differently than birdshot. If you shoot a methed-up home intruder with birdshot, for example, they will bleed but might not be hurt enough to go down.

Types of guns

- Pistols/revolvers/handguns are small enough to be held and fired with one hand (although you should use two). Good for close targets up to 25 yards away (23 meters), but can be effective up to 50 yards (46 meters).

- Shotguns typically require two hands and are held against your shoulder. You might have seen them use by hunters or people who shoot clay targets (the sport where people yell “pull!”) Good for targets up to 50 yards away (46 m), possibly up to 75 yards (68 m).

- Rifles are large, usually requiring both hands and being held against your shoulder. Good for targets up to a mile away (1.6 km), although the most common models are meant for 100-400 yards (91-365 m).

The type of ammo used is typically dependent on the type of gun. Shotgun ammo is always limited to just shotguns. Most pistol and rifle ammo is separate, although there’s a few options that are used in both types.

Since the ammo and goals/role are unique for each category, this is often one of the first decisions new gun owners have to make. Some people might choose a pistol because it’s cheap, simple, and easy to carry, for example, while others might choose a rifle because it’s more versatile and powerful.

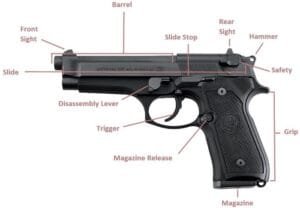

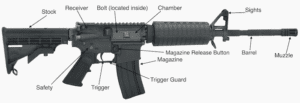

Basic gun terms/parts

It’s easy to get in the weeds on all of the little parts and names, but here’s the big stuff you should know as you learn more, make your first purchase, and navigate local laws:

-

- Stock is the part that extends back towards your shoulder, with a “butt” on the end where it makes contact with your body.

- The barrel is the portion from where the unfired bullet sits through the muzzle opening where it flies out.

- Chamber is the spot where an unfired but loaded bullet sits, waiting.

- Hammer, striker and firing pin are the pieces that strike the cartridge primer, igniting the gunpowder.

- Rear and front sights, which are built into the frame, versus optics/scopes that are added separately.

- Rails are parts of the frame that make it easy to attach accessories.

- Magazine and magazine well (where the magazine slides and clicks into). A magazine release is a button you press to drop the magazine out from the frame.

- The grip is where you hold with your dominant hand. A foregrip is an accessory or part of the frame in front of the trigger where you place your off-hand for added stability.

Local gun laws are part of why it’s handy to know these names. Instead of making laws that focus on bad people and what causes them to do bad things, many governments instead regulate the specific mechanical pieces and designs for everyone.

For example, in most places, you are not allowed to own a rifle with a barrel less than 16” unless you go through special background checks. And part of what makes the legal difference between a rifle with a short barrel and a pistol with a long barrel is the buttstock — if a gun has a buttstock you hold to your shoulder (creating three points of contact vs. a pistol’s two), it’s generally classified as a rifle and subject to those laws.

Similarly, some places limit or prohibit the use of vertical foregrips or detachable magazines. So if you find yourself in a place like California, you’ll need to learn how local laws regulate “evil features.”

How guns work

Guns work similarly to a car engine:

- Fuel is put into a small enclosed space (the piston-cylinder).

- The enclosed fuel is then ignited by the spark plugs.

- Explosions create gas and energy that wants to rapidly expand outwards.

- But since it’s an enclosed space, where does that gas/energy go?

- Engines are designed so that there’s only one direction that energy/gas can go — by pushing the piston away from the explosion.

- The force pushing the piston away is what eventually turns the axle and tires.

That “create an explosion in a tight space with only one way to escape” model is the same for firearms.

When you pull the trigger, a mechanical striker or firing pin hits the primer on the bottom/back of a round, sparking the explosion inside the casing. The explosion pushes against the back of the bullet (or the wad in a shotshell), forcing it to separate from the casing.

That energy keeps building as it continues pushing down the barrel. That’s why you might see “muzzle flashes” or small flames coming out of the end of the barrel as the bullet escapes — that’s the leftover gas quickly burning off now that it has room.

In fact, that’s why bullet speed and barrel length are often correlated. The more time a bullet and the gas/energy behind it are kept in that one-way-escape tube, the more time the bullet has to gain speed (and stability) before the energy is dispersed in the air.

Single-shot vs. semi-auto vs. full auto

What happens after the explosion pushes the bullet/shot out of the barrel? There has to be some kind of reset to eject the leftover casing and make room for a new round to fire. How that happens is the difference between labels like semi-auto or full-auto.

Think about the old-school guns used back in the 1700-the 1800s. You’ve seen in movies how people would fire one shot, then take an absurd amount of time to reload the gun. Fire, manually reload fire, manually reload, repeat.

Those are single-shot guns. The gun doesn’t “do” anything else once it’s fired. You have to do a physical movement with your hand to eject the old round and bring in a new one.

There are still guns like that today. The main benefit is better accuracy since there are fewer moving pieces during the explosion, which should (in theory) help keep the muzzle more stable. That’s why most precision rifles are single-shot “bolt-action” guns.

In a car engine, the momentum gained from the first explosion is what helps the machine rotate around and reset itself for the next cycle.

The fundamental innovation that took us from 1800s-style guns to modern weapons is similar. Instead of letting the gas-only escape in one direction (out the barrel), designers add a second escape path in the opposite direction. Newton’s Third Law of Physics says every action has an equal and opposite reaction. So the same force pushing the bullet towards the front is also pushing backward towards your body.

Semi-automatic and fully-automatic guns take advantage of that rearward force, using it to perform other mechanical actions such as physically ejecting the just-fired waist casing. So it becomes a loop that feeds and resets itself every time a bullet is fired.

This brings us to semi-auto versus full-auto:

- Semi-automatics reset themselves after firing around, but then they sit there, waiting for you to pull the trigger again.

- Full-automatics will keep cycling through the loop as long as the trigger is held down. Similar to how your car engine keeps cycling as long as you have your foot pressed down.

A well-trained person using a semi-auto gun in ideal conditions can fire up to 100 rounds per minute. In reality, you might max out at 40-50 rounds per minute (and even then you’ll be limited by magazines etc.)

Full-auto guns can shoot hundreds or even thousands of rounds per minute — just like a car engine that can cycle thousands of times per minute.

But that’s why full-auto guns are illegal basically everywhere. If you have to pull the trigger for each bullet, that theoretically makes things ‘safer’ than if you could just squeeze once and send a lot of bullets firing very quickly.

There are some minor exclusions for older grandfathered weapons (eg. built before 1986), but you have to pay a huge amount of money, go through years-long background checks, your home can be searched at any time without a warrant, you can’t cross state lines without permission, etc. It’s extraordinarily rare for a full-auto weapon to be used in a crime.

Single action vs. double action

Cocking a gun is the process of putting the hammer or striker (basically the same thing) in a spring-loaded position, so that when you pull the trigger, that hammer/striker can fly forward to hit the ammo primer and cause a spark.

So there are two mechanical actions here: spring-loading the striker, and then pulling the trigger to release it.

A weapon will be classified as a single action or double action based on whether or not you can do both of those actions in one mechanical motion, or if you have to use your hand to physically cock the gun before pulling the trigger.

Classic revolvers have the hammer protruding out the back, so you can use your thumb to cock the weapon. This gif shows a single action:

A double-action firearm is one where you can both cock and release the hammer/striker with just a trigger pull. The first part of the trigger pull cocks the hammer, while the end of the pull releases it. That means you can take a gun from uncocked to cocked and fire with just one finger pull.

Notice how this double-action trigger cocks the hammer back before firing it

For most of the weapons, you’ll use, this only matters for the first trigger pull (taking the gun from cold to hot) because the semi-auto reset cycle will cock the trigger for your follow-up shots. That means you might have a double-action gun that uses on the first pull but then becomes a SA on the following pulls.

Assault rifles, assault weapons, and AR15s vs AK47s

We’re specifically calling out assault rifles and AR-15s because there is a ton of disinformation in gun conversations (both innocent and intentional).

First, there is no real definition for an “assault weapon” — it’s simply a made up term people use for guns they think are more dangerous than others. Even though two different models might use the same type of bullet that has the same type of power, speed, and capacity, weapons that look like they’re from the military or an action movie often look scarier to people who don’t understand. They’re sometimes referred to as “black guns” because they tend to be a solid black color and made entirely of metal, instead of a more traditional wood design, and that somehow looks more dangerous.

It’s true that some guns have more destructive potential than others. A small revolver, for example, is not designed for large-scale self-defense the way an AR-15 is. But people often let perceptions override logic.

“Assault rifle” does have a definition, but almost everyone misuses the label. In reality, an assault rifle must have certain criteria, such as “select fire” functionality that lets the user switch from semi-auto to full-auto mode — but those features are already very strictly controlled by law and mostly left to the military and law enforcement, so very few civilians actually have an assault rifle.

A civilian AR-15 is a specific type of semi-automatic rifle. The AR does not stand for Assault Rifle. It actually stands for ArmaLite, the company that first designed them. Over time it became the most popular rifle platform in the western world and hundreds of companies now make their own variations of the AR-15 design. You can buy an AR-15 part from one company and it will usually work with an AR-15 part from another company.

So the name AR-15 has become one of those ubiquitous names like Tylenol or Xerox, and it morphed over time to mean any rifle based on that design. Many ignorant media reports will even refer to “scary” guns as an AR-15 even though the specific model is not even in the same category.

An AK-47 is basically the Russian equivalent of the AR-15. It has some design differences (the parts are not interchangeable) but fulfills essentially the same role. The AK-47 was cheap to make and maintain, which was important in the Soviet Union. It became very popular in the former Soviet countries and has since spread on the black market to be the weapon of choice for Middle Eastern terrorists, African warlords, etc.

Suppressors and “silencers”

What movies call “silencers” are actually called suppressors — mostly because you can’t make an explosion silent, you can only muffle it.

Remington 700 single-shot rifle with a suppressor on end of Barrell

Adding a suppressor (or “can” in slang) to a firearm does not make it whisper silent. At best, a suppressor will reduce the overall noise to a level that won’t medically hurt your ears and it eliminates the sonic boom created by some faster-than-sound bullets.

For example, many people’s “bedside gun” uses a naturally-quieter weapon/caliber paired with a suppressor. That way if you have to fend off a home invader, you don’t blow out your and your family’s eardrums or have to rely on putting on earmuffs in the moment.

In yet another example of the disconnect between reality and the fear/media/legislation around firearms, suppressors are heavily regulated in the US under NFA laws because of this perception that suppressors somehow make the public less safe. This comes in part from movie tropes about stealthy assassins with whisper-quiet pew pews, even though there are no data to suggest can correlate with violence.

Contrast that with Europe — which generally has much stricter gun laws than the US — where you can just buy a suppressor over the counter without any fuss.

That’s because the only real value of a can is to make shooting safe on the ears. That’s why some in the US Congress are trying to pass the Hearing Protection Act.

Odyssey has been the lead content writer and content marketer. He has vast experience in the field of writing. His SEO strategies help businesses to gain maximum traffic and success.